Over the last couple of years there have been books and bills introduced to establish Roaming Right in Anglo-American jurisdictions. Roaming Rights were denied in the colonies on the grounds that indigenous people had to be cleared from the land to make way for colonial extraction. As contested as they were and are, Roaming Rights were established for indigenous populations in treaties between colonial and indigenous governments, however.

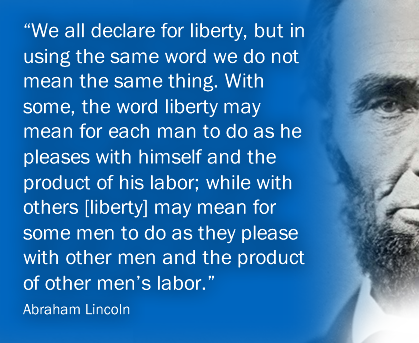

The racist, colonial denial of universal Roaming Right in Anglo-American law produces an unjust conflation between private land required for living, such as a house, a yard, and a garden, and mass-acreage land privately owned, for example in land speculation, for the accumulation of social power over other citizens, rival rentier capitalists, and global markets. In Marxist terms, this (im)moral conflation reflects the power-blind liberal conflation of capitalist use value–profit–with general use values, which legitimates sovereign-consumer and consumer-market choice arguments, private monopoly and collusion, corporate deregulation, inequality, and general capitalist Best of All Possible Worlds assumption/argumentation. Under this ruling and codified conceptual conflation, even homes have been used in apartheid settler societies not for shelter (use value), a necessary minimal condition of health, enjoyment and development, but as assets (capital) permitting Whites and global economic victors to claim intergenerational wealth over, power over, and capacity to exclude Blacks and smallholders.

This conceptual blindness is the vehicle through which inequality produces inegalitarianism, despite liberalism’s formal subscription to the former and proscription of the latter. While it brings liberalism to coalesce with conservatism, liberalism’s formal separation of inequality and inegalitarianism keeps liberalism able to co-opt the exhausted portions of its egalitarian opposition, and better able to maintain law; in this way, while it’s less immediately appealing than conservative exceptionalism, liberalism can ultimately outcompete raw conservatism, devoted to inequality, inegalitarianism, and exceptionalism. Or, liberalism and conservatism together create a system-stabilizing oscillation of strategies that pragmatists and true-believers alike can insert themselves into.

Because of this lack of conceptual distinction, for a long time, the incapacity to recognize a public interest in cross-population, sustainable use of land and water supported an inegalitarian elite-settler coalition dedicated to absolute, exclusive private property in liberal societies. This institutionalized blindness to public interest, this inegalitarianism can be observed every day in financial apartheid advertisements for gated rural and suburban property and Poor Door urban real estate property, in excluding curtains and punitive air travel policies corralling most travelers, and in the enduring public goods and services poverty of historical slavery counties. It sustains a socialized inability to distinguish depletion activities on land and water from sustainable activities. This apartheid-society conceptual incapacity was useful for establishing colonies as premier global sites of unfettered resource extraction and unfree labor exploitation and expropriation.

Restoring Collective-action Capacity and Freedom in Rural Tributaries

In the latter-day context of global monopoly capitalism, with its institutionalized wealth cores and tributary peripheries, these conceptual incapacities, codified in law, strongly undermine the freedom and reproductive capacity of non-elite, smallholder settlers. It is another case where in the multi-generational run, non-elite settlers would have been better off in coalition with peasantified indigenous people and enslaved workers than serving as grunts for elite colonial interests, under the hope that their own patrimony would be protected, not by a politically- and socially-constructed status such as citizenship, but by a magical, mythical identity conferred only at elite convenience–White Ownership.

To start off with, as discussed above, smallholders’ interests–in securing living space and life enjoyment in balance with others–are not reducible to or stably, largely compatible with mass-property owning rentier-capitalists’ interests in mining wealth for the exclusive, advantageous accumulation of social power and control over other citizens, over rival rentier capitalists, and over global markets. Whiteness politics are the result of a naive, excessive belief in the munificence and durability of economic elites’ instrumentalist marketing campaigns. But as the recent mass primitive accumulation of New Zealand, the Canadian West, and particularly the US West demonstrate, even Christian Texan billionaires–raised as Masters of Whiteness sacralization and politics–will not maintain White coalition in all those places where non-Whites have already been cleared from the land (Turkewitz 2019). If you cannot count on even Evangelical Texas oil-extractionist billionaire patriarchs for White protection, do you think it’s a good social contract option for you to buy into?

As a mystical moral exclusion, a promise of inclusion in an exclusive coalition with ruthless, teeth-baring elites, the White political construction was always designed to be land-owning elites’ paw of control over a traumatized, fearful population, for elites’ own political benefit, if variably distributing lesser resources to a malleable “White” “police” force. The broad Whiteness elite-“police” coalition is easily scrapped–in England, but just as well in the militarized, surveillance-embedded settler colonies–in favor of the narrower elite-police employer relationship in Nightwatchman societies. Today’s capital-intensive, tech-addled Nightwatchman policing relationship with exclusive, absolute, mass private property severely curtails non-elite freedom and enjoyment–from snowmobiling to fishing to hunting, to cross country skiing, mushroom gathering, forest bathing, walking, clean-water swimming, stargazing, fresh air, and so on–outside of capitalism’s expensive urban metropole commodity market.

Roaming Right & Freedom of Movement, Right of the “Starving” Man in an Excluding, Privatized World Economy

In Europe, Roaming Rights were codified in law in the mid-20th century (In England, they were codified in liberal law in 2001). They distinguish the exclusionary space needed for living–the yard, garden, house, barn, garage–from the larger, decommodified space required for people, the public, to both modestly supplement private life and enjoy sustainable use of the political-territory’s land: hiking, fishing, swimming, boating, horse watering, berry gathering, and camping rights, etc. Roaming Rights assume that people are living, reproducing, developing Earthlings, and therefore the public needs to traverse–move freely–and enjoy life in a social, balancing, non-depleting manner. This assumption is not shared by property right law, built for perpetual conquering (See the influential, founding formulations of property right and its underlying assumptions, forwarded by liberal-conservative theorists including Hobbes, Grotius, and Burke’s later reconciliation with capitalist liberalism, etc.). Roaming Right corrects property right and its antihuman excesses.

Organizing for Roaming Rights is important in the settler colonies today because inequality has grown to the point where settlers are financially excluded from global rentier capitalism’s metropoles, while at the same time they are losing access to the dispersed resources required to live and enjoy life in the tributary regions. In this context, tributary settler-indigenous coalition is vital. After all, and all pretty mystifications aside, how are indigenous people made? Indigenous people are not another, animal-like species or colorful otherworldly visitation, as political discourse has predominantly constructed them. Whatever their history and culture, the indigenous have been repeatedly constructed, and will be made out of the raw material of people again, by imperialists prohibiting indigenous people’s free movement and access to the necessities and enjoyment of life outside of inaccessible, commodified, commercial cities. Race is network boundary construction, and it’s not been as tight or class-distinguishing a boundary as wealth accumulators prefer. Today’s FIRE (Finance, Insurance, Real Estate industry) and surveillance and military tech do the exact same function, tighter.

Every capitalist elite is afraid of working class settlers and smallholders recognizing that they can be made indigenous or enslaved. To some extent this is an honest, liberal fear, because many smallholding settlers have, with but a little elite threat/encouragement, moved from that sociological, historical realization to “Better you than me” imperial warfare against indigenized people, the enslaved, and descendents thereof (See Wilson 1976).

But that honest fear has always been in coalition with the much more self-interested elite fear that other smallholding settlers will coalesce politically with the indigenized, the enslaved, and their descendants. By suppressing non-elite organic intellectuals, we have hardly come to terms with this liberal-conservative elite coalition, the imperial “civilized” bloc, and its ravaging effects.

Instead, apartheid society is fed a nonstop stream of conservative and liberal high and low cultural enforcement, cementing us apart along the difference-justice telos: Whites must know only their unjust, isolated historical place. Reified, stylized, Black positionality, Black Exceptionalism will carry difference justice (as that is reduced to liberal Dem Party political rentier strategy). In the UK, this quasi-historical (permitting recognition of heritage, but prohibiting recognition of ongoing social construction, social reproduction) cultural pseudo-speciation is further reinforced through regional class distinctions.

…

The Primitive Accumulation of the US West in the 21st Century

From Turkewitz 2019: “In the last decade, private land in the United States has become increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few. Today, just 100 families own about 42 million acres across the country, a 65,000-square-mile expanse, according to the Land Report, a magazine that tracks large purchases. Researchers at the magazine have found that the amount of land owned by those 100 families has jumped 50 percent since 2007.”

The fracking-lord Wilks brothers “who now own some 700,000 acres across several states, have become a symbol of the out-of-touch owner. In Idaho, as their property has expanded, the brothers have shuttered trails and hired armed guards to patrol their acres, blocking and stymying access not only to their private property, but also to some publicly owned areas…The Wilks brothers see what they are doing as a duty. God had given them much, Justin said. In return, he said, “we feel that we have a responsibility to the land.”

“Gates with “private property” signs were going up across the region. In some places, the Wilkses’ road closings were legal. In other cases, it wasn’t clear. Road law is a tangled knot, and Boise County had little money to grapple with it in court. So the gates stayed up.

…The Wilks family hired a lobbyist to push for a law that would stiffen penalties for trespass…

The problem, said Mr. Horting, “is not the fact that they own the property. It’s that they’ve cut off public roads.”

“We’re being bullied,” he added. “We can’t compete and they know it” (Turkewitz 2019).

As well, financial institutions started dispensing with land titling a few years ago, so in the post-2007 property grab, claims on property are going to fall to might rather than right. It’s a new mass primitive accumulation offensive.

Climate Crisis, Unproductive Capital, & Elite Rentier Strategy

While they let their Republican henchmen lull the peasantry with squeals of “No climate crisis” for decades, billionaire rentier capitalists shifted quietly into land-capturing overdrive.

“Brokers say the new arrivals are driven in part by a desire to invest in natural assets while they are still abundant, particularly amid a fear of economic, political and climate volatility.

‘There is a tremendous underground, not-so-subtle awareness from people who realize that resources are getting scarcer and scarcer,’ said Bernard Uechtritz, a real estate adviser” (Turkewitz 2019).

The Persistent Role of Moralism in Expropriation

Moving into extractive fracking from a Texas religious franchise, the Wilks Bros provide a strong example of how extractivism and expropriation is buttressed by moralism.

While buying political and legal cover, they continually assert that their antisocial land speculation offensive is mandated by God, sacralizing their self-interested conflation of smallholder living space with their own, exclusionary mass capture of land.

Expropriative, Gilded-Age Restoration: Separating Out Global Rentier Capitalists’ Interests from Smallholder Interests

TBD

The Urbanite’s Interest in Roaming Right

Why would an urbanite care about Roaming Right? After all, urbanites are precisely the people who have forfeited Roaming Right in favor of obtaining all their life reproduction needs and enjoyment through the concentrated commodity market of the city, and by proximity to self-interested elite infrastructure. As Mike Davis and Cedric Johnson (2019) clarify, the cosmopolitan eschews the public. Relatedly, the condition of inequality-restoration urbanity, the engine of global monopoly capitalism, is the denial of capitalism’s reproductive dependence upon its sea of expropriation. A city is built on legalized, overlapping claims on future wealth creation, but the ingredients to that wealth creation are not exclusively to be found in the city.

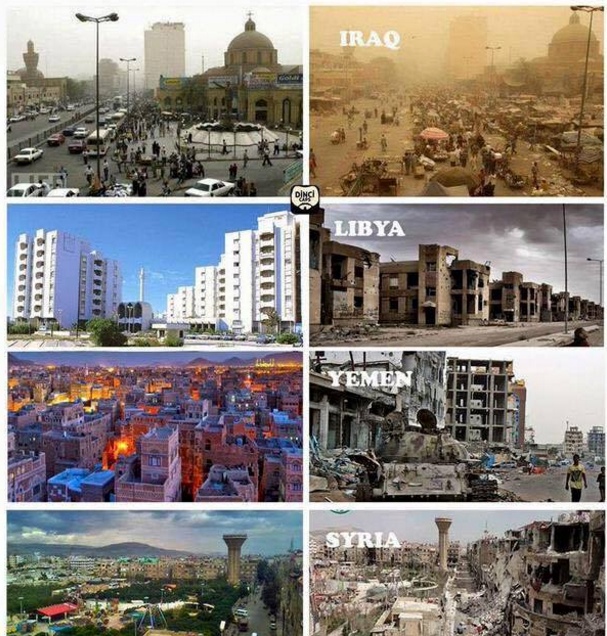

Urban intellectuals and social workers recognize that denial extremely partially, as “gentrification.” Those who cannot live on 100% commodified life, the poor, are removed out of sight from the metropole. Yet at the same time, within and across borders, the tributary countryside is enclosed by global billionaires, and the people in that periphery are shoved to the smallholding margins, left without wealth, without access to fully-commodified life (which affordability, which wage-consumption urban economy depends on rural decommodifications, cheap inputs), or access to non-commodified life reproduction or enjoyment. They are expelled, set marching, set reeling. We admire how they’ve chosen us when they alight amongst us to serve us. Or we demand to speak to the manager. As in past Primitive Accumulation offensives, itinerancy is criminalized, and imperial militarization and an international for-profit carceral industry rages like a climate-crisis Firenado.

In this context, wouldn’t it be more natural, an efficient division of political labor, for urbanites to focus on getting Democrats (or Liberals or NDP) elected to office? Meanwhile urbanites can wait for deprived, low-density rural populations to organize their own solution to their desperate lives. After all, in those moments when those rural folks were organized and slightly-patronized by big owners (See Wilson 1976), they should have seen the limits of the inequality coalition…like wage-earning urbanites do? Something seems to be impeding organization. Perhaps, just perhaps, it’s that massive surveillance, policing, and carceral apparatus (Johnson 2019).

Cities depend on tributaries for most of the raw materials of life bought on the urban market. As well, they depend on using the countryside as an urban waste sink. A pervasive lack of recognition of the non-autonomy of the city, urban commodity fetishism, including imagining the enjoyments–museums, libraries, bars and restaurants, dance venues, art galleries, theatres, orchestras, ballet troupes, poetry nights, etc.–as the sui generis private-collective property of the city, the lack of conceptualization of how the cheap raw-material market goods come to appear in the city and how wastes disappear from the city, leads to pervasive political mis-analysis.

If cosmopolitans around the world want to stop being ruled by Donald Trump and like politicians, if they want to enjoy the free expression of their cosmopolitan merit, they need to use their geographic concentration as an organization asset to break down the marginalization, the peasantification of the countryside domestic and international, the remnant alignment between rural -tributary smallholders and global rentier capitalists–particularly in an unfree time in which those rentier capitalists are aggressively excluding rural settlers from enjoyable rural life and yet inequality, including tight metropole police exclusion of indigents, prohibits mass rural-urban mobility.

Artwork by Fernando Garcia-Dory & Amy Franceschini

As beholden as their enjoyment and their identities are to FIRE (Finance Insurance Real Estate capital) patronage and cheap commodity inputs and waste sinks, urbanites need to organize, to reconstruct a smallholder Red-Green alliance traversing the urban-rural divide, and taming private property right, as Swedes did at the turn of the Twentieth Century to establish an effective, semi-independent social democracy. Roaming Right is a great coalition vehicle for such a democratic realignment and legal revolution. City people should use their structurally-superior communication and organization capacity to reach out and help rural people–across race and gender–to secure–but not mine–the non-commodified world they need to live and enjoy themselves, through universal Roaming Right. Recognizing that the past half century of rural expulsions transcends national boundaries, Red-green political coalition could be the “close to home” foundation of internationalist capacity, rather than mere consumption cosmopolitanism.

You Are What You Enjoy: Identity, Alienation, & Inegalitarianism in Capitalism

TBD

Bibliography

Greens of British Columbia. 2017. “Weaver introduces Right to Roam Act.”

Ilgunas, Ken. 2018. This land is our land: How we lost the right to roam and how to take it. Plume Press.

Johnson, Cedric. 2019. “Black political life and the Blue Lives Matter Presidency.” Jacobin, February 17.

Turkewitz, J. 2019. “Who gets to own the West?” The New York Times, June 22.

Wikipedia. “Freedom to Roam.”

Wilson, William Julius. 1976. “Class conflict and segregation in the Postbellum South.” Pacific Sociological Review 19 (4): 431-446.